Lucy Webb Hayes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lucy Ware Hayes (

In 1850, Rutherford's older sister Fanny Platt encouraged him to visit with Lucy again. That summer Lucy was 19, and she and Rutherford were members of the same wedding party. Rutherford was so taken with Lucy that he gave her the prize (a gold ring) that he had found in the wedding cake.

In 1851, Rutherford wrote in his diary, "I guess I am a great deal in love with L(ucy). ... Her low sweet voice ... her soft rich eyes." Rutherford also praised her intelligence and character, "She sees at a glance what others study upon, but will not, perhaps study what she is unable to see at a flash. She is a genuine woman, right from instinct and impulse rather than judgment and reflection."

After the couple became engaged, Lucy returned the wedding cake ring to Rutherford. He wore that ring for the rest of his life.

Lucy and Rutherford were married at her mother's house in

In 1850, Rutherford's older sister Fanny Platt encouraged him to visit with Lucy again. That summer Lucy was 19, and she and Rutherford were members of the same wedding party. Rutherford was so taken with Lucy that he gave her the prize (a gold ring) that he had found in the wedding cake.

In 1851, Rutherford wrote in his diary, "I guess I am a great deal in love with L(ucy). ... Her low sweet voice ... her soft rich eyes." Rutherford also praised her intelligence and character, "She sees at a glance what others study upon, but will not, perhaps study what she is unable to see at a flash. She is a genuine woman, right from instinct and impulse rather than judgment and reflection."

After the couple became engaged, Lucy returned the wedding cake ring to Rutherford. He wore that ring for the rest of his life.

Lucy and Rutherford were married at her mother's house in

On December 31, 1877, Rutherford and Lucy celebrated their

On December 31, 1877, Rutherford and Lucy celebrated their  Lucy frequently accompanied her husband on trips around the country. Rutherford travelled so much that the ''

Lucy frequently accompanied her husband on trips around the country. Rutherford travelled so much that the '' When the children of Washington were banned from rolling their Easter eggs on the Capitol grounds, they were invited to use the White House lawn on the Monday following Easter.

Lucy was a friend to other First Ladies. During her tenure as First Lady, Lucy visited with Sarah Polk and journeyed to

When the children of Washington were banned from rolling their Easter eggs on the Capitol grounds, they were invited to use the White House lawn on the Monday following Easter.

Lucy was a friend to other First Ladies. During her tenure as First Lady, Lucy visited with Sarah Polk and journeyed to

Back in Ohio after leaving the White House, Lucy joined the Woman's Relief Corps (founded 1883), taught a Sunday School class, attended reunions of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and entertained distinguished visitors to

Back in Ohio after leaving the White House, Lucy joined the Woman's Relief Corps (founded 1883), taught a Sunday School class, attended reunions of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and entertained distinguished visitors to

Lucy Ware Webb Hayes

- Official White House biography

Lucy Hayes

at

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Webb; August 28, 1831 – June 25, 1889) was the wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

and served as first lady of the United States

The first lady of the United States (FLOTUS) is the title held by the hostess of the White House, usually the wife of the president of the United States, concurrent with the president's term in office. Although the first lady's role has never ...

from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes was the first First Lady to have a college degree. She was also a more egalitarian hostess than previous First Ladies. An advocate for African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

both before and after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Lucy invited the first African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

professional musician to appear at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

. She was a Past Grand of Lincoln Rebekah Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows

The Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) is a non-political and non-sectarian international fraternal order of Odd Fellowship. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Wildey in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Evolving from the Order of Odd ...

, together with her husband.

Historians have christened her "Lemonade Lucy" due to her staunch support of the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

; however, contrary to popular belief, she was never referred to by that nickname while living. It was her husband who banned alcohol from the White House.

Early life

Lucy Webb was born on August 28, 1831 inChillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Ross County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Scioto River 45 miles (72 km) south of Columbus, Chillicothe was the first and third capital of Ohio. It is the only city in Ross Count ...

. Her parents were Dr. James Webb and Maria Cook. She had two older brothers who both became medical doctors.

In 1833, Lucy's father went to his family's home in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, Fayette County. By population, it is the List of cities in Kentucky, second-largest city in Kentucky and List of United States cities by popul ...

to free 15-20 slaves he had inherited from his aunt. There was a cholera epidemic

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organizat ...

happening at the time and James cared for the sick. Soon James became infected with cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

and died. Friends of Lucy's mother advised the family to sell the slaves rather than free them. Maria responded that she would take in washing to earn money before she would sell a slave.

Maria's father, Isaac Cook, was a temperance advocate and he encouraged young Lucy to sign a pledge to abstain from alcohol.

The Webbs were Methodists.

Education

In 1844, the Webb family moved toDelaware, Ohio

Delaware is a city in and the county seat of Delaware County, Ohio, United States. Delaware was founded in 1808 and was incorporated in 1816. It is located near the center of Ohio, is about north of Columbus, and is part of the Columbus, Ohio m ...

. Lucy's brothers enrolled at Ohio Wesleyan University

Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) is a private liberal arts college in Delaware, Ohio. It was founded in 1842 by methodist leaders and Central Ohio residents as a nonsectarian institution, and is a member of the Ohio Five – a consortium ...

. Although women were not allowed to study at Wesleyan, Lucy was permitted to enroll in the college prep program at the university. A term report signed by the vice-president of Ohio Wesleyan

Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) is a private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Delaware, Ohio. It was founded in 1842 by methodist leaders and Ohio Valley, Central Ohio residents as a nonsec ...

in 1845 noted that her conduct was "unexceptionable" (beyond reproach).

Several months later Lucy transferred to Cincinnati Wesleyan Female College and she graduated from there in 1850. Lucy was unusually well educated for a young lady of her day.

While in college, Lucy wrote essays on social and religious issues. One essay was entitled "Is Traveling on the Sabbath Consistent with Christian Principles?" At her commencement, she read an original essay, "The Influence of Christianity on National Prosperity." Lucy appears to have been influenced by the women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement, writing in one essay, "It is acknowledged by most persons that her (woman's) mind is as strong as a man's. ... Instead of being considered the slave of man, she is considered his equal in all things, and his superior in some."

Marriage

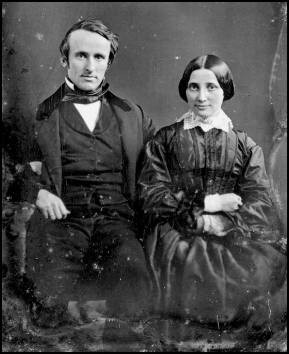

Lucy first metRutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

at Ohio Wesleyan University

Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) is a private liberal arts college in Delaware, Ohio. It was founded in 1842 by methodist leaders and Central Ohio residents as a nonsectarian institution, and is a member of the Ohio Five – a consortium ...

. At the time, Lucy was fourteen years old and Rutherford was twenty-three. Rutherford's mother was hopeful that the two would find a connection, but at this point Rutherford considered Lucy "not quite old enough to fall in love with."

In 1850, Rutherford's older sister Fanny Platt encouraged him to visit with Lucy again. That summer Lucy was 19, and she and Rutherford were members of the same wedding party. Rutherford was so taken with Lucy that he gave her the prize (a gold ring) that he had found in the wedding cake.

In 1851, Rutherford wrote in his diary, "I guess I am a great deal in love with L(ucy). ... Her low sweet voice ... her soft rich eyes." Rutherford also praised her intelligence and character, "She sees at a glance what others study upon, but will not, perhaps study what she is unable to see at a flash. She is a genuine woman, right from instinct and impulse rather than judgment and reflection."

After the couple became engaged, Lucy returned the wedding cake ring to Rutherford. He wore that ring for the rest of his life.

Lucy and Rutherford were married at her mother's house in

In 1850, Rutherford's older sister Fanny Platt encouraged him to visit with Lucy again. That summer Lucy was 19, and she and Rutherford were members of the same wedding party. Rutherford was so taken with Lucy that he gave her the prize (a gold ring) that he had found in the wedding cake.

In 1851, Rutherford wrote in his diary, "I guess I am a great deal in love with L(ucy). ... Her low sweet voice ... her soft rich eyes." Rutherford also praised her intelligence and character, "She sees at a glance what others study upon, but will not, perhaps study what she is unable to see at a flash. She is a genuine woman, right from instinct and impulse rather than judgment and reflection."

After the couple became engaged, Lucy returned the wedding cake ring to Rutherford. He wore that ring for the rest of his life.

Lucy and Rutherford were married at her mother's house in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

in a simple ceremony on December 30, 1852.

They spent their honeymoon at Fanny's house in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

, before returning to Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

. In Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

, Rutherford argued a case before the Ohio Supreme Court

The Ohio Supreme Court, Officially known as The Supreme Court of the State of Ohio is the highest court in the U.S. state of Ohio, with final authority over interpretations of Ohio law and the Ohio Constitution. The court has seven members, a ...

while Fanny and Lucy developed a close friendship. The two women attended lectures and concerts together. Lucy and Fanny once went to a lecture by noted suffragette Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

. Lucy Hayes agreed with Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

that a reform in the wage scale for women was long overdue, and that "violent" methods sometimes served the purpose of calling attention to the need for reforms. Lucy noted that Stone took the position that "whatever is proper for a man to do is equally right for a woman provided she has the power." According to Emily Apt Geer of the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center

The Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center is a complex comprising several buildings related to the life and presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. It is the first presidential library, built in 1916, and one of three such libraries for US presidents ...

, "if the influence of the bright and aggressive Fanny Platt had extended over a normal lifetime, Lucy Hayes might have become active in the woman's rights movement." Fanny Platt died in childbirth during the winter of 1856. Lucy named her sixth child and only daughter Fanny in memory of her sister-in-law and friend.

The couple had eight children: Birchard Austin (1853–1926), Webb Cook (1856–1934), Rutherford Platt (1858–1927), Joseph Thompson (1861–1863), George Crook (1864–1866), Fanny (1867–1950), Scott Russell (1871–1923), and Manning Force (1873–1874).

Rutherford had previously thought the abolition of slavery was too radical an action. But, influenced by Lucy's anti-slavery sentiments, soon after their marriage Rutherford began defending runaway slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery in the United States, slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, Fugitive Slave ...

in court who had crossed into Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

.

After Lincoln's election in 1860, Lucy and Rutherford joined the presidential train from Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

to Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

.

Civil War

When the first news of the firing onFort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

reached Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Lucy was in favor of the war. She felt that if she had been at Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

with a garrison of women, there might not have been a surrender. Her enthusiasm encouraged Rutherford to enlist as a major in the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry. As often as she could, Lucy – sometimes with her mother and children – visited Rutherford in the field. She often assisted her brother, Dr. Joe Webb, in caring for the sick.

In September 1862, Rutherford was injured in battle in Middleton, Maryland. Thinking he was hospitalized in Washington due to a paperwork error, Lucy rushed to the nation's capital. She eventually found Hayes in Maryland and after two weeks of convalescence, the Hayeses returned to Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, traveling by train with other wounded troops.

After Rutherford returned to his regiment, Lucy became a regular visitor in Rutherford's Army camp. She ministered to the wounded, cheered the homesick, and comforted the dying. She also secured supplies from Northern civilians to better equip the Union soldiers. Lucy was often joined by her mother at camp and her brother Joe was the regiment's surgeon. The men of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry affectionately nicknamed her "Mother Lucy" for her service. At one point, twenty-year-old William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

spent hours tending a campfire because Lucy sat nearby.

The couple's infant son, Joe, died while the family was at an Army camp.

Congress

While Rutherford served in Congress, Lucy joined him in Washington for its winter social season. Lucy regularly sat in the gallery of the House to listen to congressional debates. She often wore a checkered shawl so her husband could spot her. In 1866, the Hayeses and other congressional couples visited the scene of race riots inMemphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

to see the damage that had been done.

She also worked for the welfare of children and veterans. The couple's nearly two-year-old son George died during this period.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

First Lady of Ohio

While Rutherford wasGovernor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, Lucy often accompanied her husband on visits to prisons, correctional institutions for boys and girls, hospitals for the mentally ill, and facilities for the deaf and mute.

In 1870, Lucy and her friends established a soldiers' orphans home in Xenia, Ohio

Xenia ( ) is a city in southwestern Ohio and the county seat of Greene County, Ohio, United States. It is east of Dayton and is part of the Dayton Metropolitan Statistical Area, as well as the Miami Valley region. The name comes from the Greek l ...

.

Rutherford initially chose not to run for a third term as governor and in 1873, the family moved to Spiegel Grove

Spiegel Grove, also known as Spiegel Grove State Park, Rutherford B. Hayes House, Rutherford B. Hayes Summer Home and Rutherford B. Hayes State Memorial was the estate of Rutherford B. Hayes, the nineteenth President of the United States, locate ...

. Rutherford's uncle, Sardis Birchard, had built the house years earlier with them in mind. This house would later become the first presidential library.

In 1875, Rutherford ran for and won a third term as governor. The hard fought victory brought Rutherford to national prominence. In June 1876, he was nominated for president by the Republican party.

Lucy played an active role in her husband's administration and lobbied the state legislature to provide more funding to schools, orphanages, and insane asylums.

Their youngest child, named for General Manning F. Force, was born in 1873 and died in 1874, while the Hayes family lived at Spiegel Grove.

First Lady of the United States

The presidential election of 1876 was one of the most controversial in the country's history. Hayes was not declared the winner until March 1, 1877, five months after Election Day. The declaration was so delayed that the Hayes family boarded a train toWashington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

without being sure if Rutherford was the president elect. The next morning, March 2, they were awakened near Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the List of c ...

to receive the news that Congress had finally declared Hayes President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

.

In the early days of Rutherford's administration, the North's military occupation of the South and the Reconstruction era came to an end.

Restoration funds for the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

were unavailable when they first moved in, so Lucy retrieved old furniture from the attic and rearranged things to hide the holes in the carpets and drapes. According to executive assistant William Cook, "any really good things owed their preservation to this energetic lady."

By the time of Rutherford's inauguration, the position of First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

was an increasingly prominent one. There were growing numbers of female journalists in the late nineteenth century. Female reporters devoted much of their time and energy to covering the most visible woman in America: the First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

. The attention began after Rutherford's inauguration, with the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' writing "Mrs. Hayes is a most attractive and lovable woman. She is the life and soul of every party ... For the mother of so many children she looks ... youthful."

Lucy Hayes was the first wife of a President to be widely referred to as the First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

by the press, when Mary Clement Ammes referred to the "First Lady" in a newspaper column about the inauguration. Advances in printing technology meant that a wide audience saw sketches of the new First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

from the 1877 inauguration.

At this time it was not the custom for a president's wife to have a staff of social assistants and, unlike some previous First Ladies, Lucy had no adult daughters to help shoulder the workload. Lucy depended on nieces, cousins, and daughters of friends to help with social events, and these young ladies also helped enliven the Hayes White House.

Lucy was fond of animals. A cat, a bird, two dogs, and a goat joined the Hayes family in residence at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

.

In 1879, ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' described Lucy's dress at the White House New Year's Reception, "The dress of Mrs. Hayes was at once simple and elegant ... With accustomed good taste she wore no jewelry, and the white plume in her black hair fell gracefully in drooping folds."

At the first official state dinner on April 19, 1877 to honor Russian Grand Duke Alexis and Grand Duke Constantine, a "full quota" of wine was served. But soon after this, President Hayes made it known that there would be no more alcoholic beverages served at future White House functions. The six wine glasses laid out at each place setting had angered temperance advocates and Rutherford believed the Republican party needed the temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

vote. The decision was Rutherford's, although Lucy may have influenced him. Although the Hayes family were generally teetotal

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

, they had previously served alcoholic beverages to guests at their home in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. But because Lucy was a known teetotaler (Hayes sometimes had a "schoppen" of beer when he visited Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

) she was blamed for the dry White House. Regardless of her teetotaler status however, along with her husband they privately opposed Prohibition. They believed controlling alcohol consumption through education and example rather than force was more effective. Yet Hayes understood the political power becoming a teetotaler gave him by ensuring dry Republicans stayed within the party. He believed this stance on alcohol would only effect them at the White House and could still enjoy in private. This political move earned they more attention than they had originally thought. As a mother herself, Lucy stood as a key figure in the temperance movement as setting an example for how women could set moral examples for their families She understood the power her role possessed and announced to the public that, “I have young sons who have never tasted liquor, they shall not receive from my hand, or with the sanction that its use in the family would give, the first taste of what might prove their ruin. What I wish for my own sons I must do for the sons of other mothers.”

Later, when President Garfield brought alcohol back the White House, the Haye's predicted it would cause a split within the Republican party.

In general, Lucy had a more casual style that was reflected in the receptions she held during Washington's winter social season. During the holidays, she invited staff members and their families to Thanksgiving dinner

The centerpiece of contemporary Thanksgiving in the United States and in Canada is Thanksgiving dinner (informally called turkey dinner), a large meal generally centered on a large roasted turkey. Thanksgiving could be considered the largest ...

and opened presents with them on Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

morning. The White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

telegraph operator

A telegraphist (British English), telegrapher (American English), or telegraph operator is an operator who uses a telegraph key to send and receive the Morse code in order to communicate by land lines or radio.

During the Great War the Royal ...

and secretaries

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

were included in the Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

group. The group was so large it took three turkeys and a roast pig to feed them all. Lucy was generally kind towards the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

staff, she also allowed White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

servants to take time off to attend school.

On December 31, 1877, Rutherford and Lucy celebrated their

On December 31, 1877, Rutherford and Lucy celebrated their silver wedding anniversary

A wedding anniversary is the anniversary of the date a wedding took place. Couples may take the occasion to celebrate their relationship, either privately or with a larger party. Special celebrations and gifts are often given for particular ann ...

in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

.

The most significant change made to the White House during Hayes' term were the installation of bathrooms with running water and the addition of a crude wall telephone. Lucy was the first First Lady to use a typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectivel ...

, a telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

, and a phonograph

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

while in office, and was also the first to enjoy a permanent system of running water in the White House.

Lucy preferred to enlarge the greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of Transparent ceramics, transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic condit ...

conservatories rather than to undertake extensive redecoration of the White House. The billiard-room, which connected the house with the conservatories, was converted into an attractive greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of Transparent ceramics, transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic condit ...

and the billiard table

A billiard table or billiards table is a bounded table on which cue sports are played. In the modern era, all billiards tables (whether for carom billiards, pool, pyramid or snooker) provide a flat surface usually made of quarried slate, that ...

consigned to the basement

A basement or cellar is one or more floors of a building that are completely or partly below the ground floor. It generally is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the furnace, water heater, breaker panel or fuse box, ...

. Shuttered windows in the State Dining Room

The State Dining Room is the larger of two dining rooms on the State Floor of the Executive Residence of the White House, the home of the president of the United States in Washington, D.C. It is used for receptions, luncheons, larger formal dinne ...

could be opened for dinner guests to look into the conservatories. Some Americans considered the billiard table as either a gambling device or a rich man's toy, and the Hayes were glad to get it out of sight.

Every day, flowers were brought in from the greenhouses to decorate the White House. Additional bouquets were sent to friends and Washington hospitals. Greenhouse upkeep made up one fourth of the White House's household expenditures under Hayes.

Looking to celebrate American flora and fauna, Lucy commissioned Theodore R. Davis to design new china for the White House. After using the pieces, Washington hostess Clover Adams complained that it was hard to eat soup calmly with a coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecologica ...

springing from behind a pine tree

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accepts ...

in the bowl.

Music was important to Lucy and, while famous musicians performed downstairs at White House events, informal "sings" occurred upstairs in the family quarters. Lucy sang and played the guitar, and was assisted by the talents of friends and family. At times, Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

played the piano while Vice President William A. Wheeler

William Almon Wheeler (June 30, 1819June 4, 1887) was an American politician and attorney. He served as a United States representative from New York from 1861 to 1863 and 1869 to 1877, and the 19th vice president of the United States from 1877 t ...

, Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

, and his brother, Gen. William T. Sherman, joined in singing gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

songs.

Lucy frequently accompanied her husband on trips around the country. Rutherford travelled so much that the ''

Lucy frequently accompanied her husband on trips around the country. Rutherford travelled so much that the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' nicknamed him "Rutherford the Rover." In 1877, The couple undertook a tour of the South in hopes of improving national unity. The ''Richmond Dispatch

The ''Richmond Times-Dispatch'' (''RTD'' or ''TD'' for short) is the primary daily newspaper in Richmond, the capital of Virginia, and the primary newspaper of record for the state of Virginia.

Circulation

The ''Times-Dispatch'' has the second ...

'' reported that Lucy "won the admiration of people where she has been."

In 1878, Lucy toured Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

without her husband. She visited the Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia School of Design for Women

Philadelphia School of Design for Women (1848–1932) was an art school for women in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Housed in the former Edwin Forrest House at 1346 North Broad Street, under the directorship of Emily Sartain (1886–1920), ...

, and the Woman's Medical College, as well as several schools and orphanages. This was the first documented instance of a First Lady following a public schedule independent of the President.

In 1880, Lucy was the first presidential spouse to visit the West Coast while her husband was President. While on their Western tour, Lucy and Rutherford met with Sarah Winnemucca

Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins ( – October 17, 1891) was a Northern Paiute author, activist (lecturer) and educator (school organizer). Her maiden name is Winnemucca.

Her Northern Paiute language, Northern Paiute name was Thocmentony, also spelled To ...

. Lucy was moved to tears by Winnemucca's impassioned speech for Native American lands.

Lucy's compassion and sincerity endeared her to Washingtonians. She regularly visited the National Deaf Mute College (today Galludet) and the Hampton Institute

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association aft ...

, where she sponsored a scholarship for a student. She continued to show concern for the poor by contributing generously to Washington charities. In January 1880 alone, Lucy and Rutherford gave $990 to help the poor in Washington.

However, Lucy rejected pleas from groups requesting her public support, committing herself instead to serving as a moral example to the nation. Rutherford once commented, "I don't know how much influence Mrs. Hayes has with Congress, but she has great influence with me."

As First Lady, Lucy advocated for the completion of the Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk shaped building within the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, once commander-in-chief of the Continental Army (1775–1784) in the American Revolutionary War and the ...

.

When the children of Washington were banned from rolling their Easter eggs on the Capitol grounds, they were invited to use the White House lawn on the Monday following Easter.

Lucy was a friend to other First Ladies. During her tenure as First Lady, Lucy visited with Sarah Polk and journeyed to

When the children of Washington were banned from rolling their Easter eggs on the Capitol grounds, they were invited to use the White House lawn on the Monday following Easter.

Lucy was a friend to other First Ladies. During her tenure as First Lady, Lucy visited with Sarah Polk and journeyed to Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington (June 21, 1731 — May 22, 1802) was the wife of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Although the title was not coined until after her death, Martha Washington served as the inaugural ...

's Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

and Dolley Madison

Dolley Todd Madison (née Payne; May 20, 1768 – July 12, 1849) was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of bo ...

's Montpelier. She asked Julia Tyler

Julia Tyler ( ''née'' Gardiner; May 4, 1820 – July 10, 1889) was the second wife of John Tyler, who was the tenth president of the United States. As such, she served as the first lady of the United States from June 26, 1844, to March 4, 18 ...

to help officiate at a White House reception and was friendly with former First Lady Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Grant (née Dent; January 26, 1826 – December 14, 1902) was the first lady of the United States and wife of President Ulysses S. Grant. As first lady, she became a national figure in her own right. Her memoirs, '' The Personal Memo ...

. She was also friendly with future First Ladies including Lucretia Garfield

Lucretia Garfield ('' née'' Rudolph; April 19, 1832 – March 13, 1918) was the first lady of the United States from March to September 1881, as the wife of James A. Garfield, the 20th president of the United States.

Born in Garrettsville, Oh ...

, Ida McKinley

Ida McKinley ( née Saxton; June 8, 1847 – May 26, 1907) was the first lady of the United States from 1897 until 1901, as the wife of President William McKinley.

Born to a successful Ohio family, Ida met her future husband and later marr ...

, and Helen Herron Taft

Helen Louise Taft (née Herron; June 2, 1861 – May 22, 1943), known as Nellie, was the wife of President William Howard Taft and the first lady of the United States from 1909 to 1913.

Born to a politically well-connected Ohio family, Nel ...

.

When portraits of past presidents were commissioned for the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, Lucy insisted that paintings of both Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington (June 21, 1731 — May 22, 1802) was the wife of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Although the title was not coined until after her death, Martha Washington served as the inaugural ...

and Dolley Madison

Dolley Todd Madison (née Payne; May 20, 1768 – July 12, 1849) was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of bo ...

also grace the walls of the presidential mansion. Lucy's own official portrait by Daniel Huntington was commissioned by the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

.

On his 48th birthday, Rutherford wrote to Lucy, "My life with you has been so happy--so successful--so beyond reasonable anticipations, that I think of you with a loving gratitude that I do not know how to express."

Rutherford kept his promise to serve only one term, the Hayes family returned to their Fremont, Ohio

Fremont is a city in and the county seat of Sandusky County, Ohio, United States, located along the banks of the Sandusky River. It is about 35 miles from Toledo and 25 miles from Sandusky. It is part of the Toledo metropolitan area. The populat ...

, home, Spiegel Grove

Spiegel Grove, also known as Spiegel Grove State Park, Rutherford B. Hayes House, Rutherford B. Hayes Summer Home and Rutherford B. Hayes State Memorial was the estate of Rutherford B. Hayes, the nineteenth President of the United States, locate ...

, in 1881.

Views on race

Lucy Hayes was an advocate forAfrican Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

both before and after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. She remained in contact with her family's former slaves, and employed some. Winnie Monroe, a former slave freed by Lucy's mother Maria, eventually moved to the White House with the Hayes family as a cook and nurse. Later, Lucy would encourage Winnie's daughter Mary Monroe to attend Oberlin.

The Hayes were so known for their sympathy towards African Americans that a month after they returned to Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

from Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

, a black baby was left on their doorstep.

In 1861, Lucy wrote to her husband, "if a contraband unaway slaveis in Camp--- don't let the 23rd Regiment be disgraced by returning im or her"

As First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

, Lucy invited African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

performers to the White House. In 1878, Marie Selika Williams

Marie Selika Williams (c. 1849 – May 19, 1937) was an American coloratura soprano. She was the first black artist to perform in the White House.

Biography

She was born Marie Smith in Natchez, Mississippi, around 1849. After she was born her fa ...

(1849-1937), also known as Madame Selika, appeared at the White House. Introduced by Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, Madame Selika was the first African-American professional musician to appear at the White House.

Views on temperance

Known as a teetotaler, Lucy had signed a pledge to abstain from alcohol at a young age. TheWhite House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

had a ban on alcoholic beverages during Rutherford's term, but historians generally credit Rutherford with the final decision to ban alcohol. Lucy actually opposed prohibition. She preferred to persuade rather than prevent and did not condemn those who used alcohol in moderation.

Lucy was not a member of any temperance groups. She resisted attempts by the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU) to enlist her as a leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

out of fear of creating political fallout for her husband by association with the controversial cause.

The WCTU paid for a portrait of Lucy by Daniel Huntington before she left the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

.

The first written references to "Lemonade Lucy" don't turn up until the 20th century, which didn't begin until 11 years after Lucy's death in 1889, according to Tom Culbertson of the Hayes Center. Hundreds of articles, cartoons, and poems chronicled and parodied her opposition to drinking. Historian Carl Anthony "suggests a reason the legend of Lemonade Lucy might have become so popular with historians of the early 20th century, when there was greater moral stigma associated with alcohol consumption".

Views on suffrage

As a young woman, Lucy expressed opinions that suggested she was pro-suffrage, but she did not join any of the prominent suffrage groups of the day. Two of Lucy's aunts were involved in the suffrage movement. Many historians believe that had her sister-in-law Fanny Platt lived longer, Lucy would have become a committed advocate for women's suffrage.Later life

Back in Ohio after leaving the White House, Lucy joined the Woman's Relief Corps (founded 1883), taught a Sunday School class, attended reunions of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and entertained distinguished visitors to

Back in Ohio after leaving the White House, Lucy joined the Woman's Relief Corps (founded 1883), taught a Sunday School class, attended reunions of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and entertained distinguished visitors to Spiegel Grove

Spiegel Grove, also known as Spiegel Grove State Park, Rutherford B. Hayes House, Rutherford B. Hayes Summer Home and Rutherford B. Hayes State Memorial was the estate of Rutherford B. Hayes, the nineteenth President of the United States, locate ...

. Lucy also became national president of the newly formed Woman's Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Church. As president, she called attention to the plight of the urban poor and disenfranchised African-Americans in the South. She also spoke out against Mormon polygamy. However, when asked by Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

to send delegates from the Home Missionary Society to a meeting of the International Council of Women, Lucy declined.

Hayes spent her last eight years at Spiegel Grove. A few days after suffering a stroke, she died, at age 57, on June 25, 1889. Flags across the country were flown at half-mast in her honor.

Rutherford died three and a half years later and was buried beside his wife. In 1915, their remains were moved to Spiegel Grove. Below them are buried their dog Gryme and two horses named Old Whitey and Old Ned.

Legacy

Lucy Hayes served as First Lady during an important transitional era in nineteenth-century American history. Major economic trends of the 1870s included the rise of national businesses, shifts in centers of agriculture, and the development of a favorable balance of trade for the United States. The accelerated movement of people from rural to urban areas also brought about great alterations in social life. She agreed with the people of the times. Emily Apt Geer explained, Spiegel Grove is operated by the Ohio History Connection and is open to the public. Hayes is honored with a life-size bronze sculpture inside the Cuyahoga County Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in Cleveland, Ohio.In popular culture

* In themusical comedy

Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, movemen ...

'' 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue'', the First Lady sings the "Duet for One," in which she transforms from Mrs. Grant into Lucy Webb Hayes.

* In the Lucky Luke

''Lucky Luke'' is a Western ''bande dessinée'' series created by Belgian cartoonist Morris in 1946. Morris wrote and drew the series single-handedly until 1955, after which he started collaborating with French writer René Goscinny. Their par ...

comic book ''Sarah Bernhardt'', which is set in the late 19th-century Wild West, President Rutherford B. Hayes's wife is portrayed as being one of many who strongly disapprove of the titular actress's tour of the United States, given her reputation for loose morality. Disguised as a man called "George," the First Lady infiltrates Sarah's entourage and sabotages their tour throughout the U.S., though she does come to accept Sarah when the French actress's charms and singing talent moves a tribe of hostile Indians. "The president's wife" is not mentioned by name in the book, and thus might be regarded as fictional, although she and her husband do resemble Rutherford and Lucy Hayes in many ways. Hayes himself is portrayed as a man who is very taken aback by his wife's hostility towards Sarah, and keeps making the same speech over and over again, even when there is no one there to listen to him.

References

External links

Lucy Ware Webb Hayes

- Official White House biography

Lucy Hayes

at

C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American cable and satellite television network that was created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a nonprofit public service. It televises many proceedings of the United States ...

's '' First Ladies: Influence & Image''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hayes, Lucy Webb

1831 births

1889 deaths

19th-century American women

19th-century Methodists

American abolitionists

Methodists from Ohio

American temperance activists

First Ladies and Gentlemen of Ohio

First Ladies of the United States

Methodist abolitionists

Ohio Wesleyan Female College alumni

People from Chillicothe, Ohio

People from Fremont, Ohio

Rutherford B. Hayes

Hayes family